Robert Adams is a quintessential example of the New Topographics school that was prominent in the 70s (see also the Bechers, Shore, Gohlke, Baltz, etc). The influences of its idea/aesthetic/sensibility remain apparent in photography today. (One needs to only replace random lonely inanimate landscapes with random lonely people.) On the other hand, another common theme on top of subject matter for the New Topographics was an absolute mastery and control of the black and white medium, which is something altogether rare today. Not non-existent, but certainly not easily found. Anyhow, even if this work Adams did in the West now seems un-extraordinary in it’s visual commonplace-ness today, there’s still much to be had from it I think.

Lyn Devon, the designer, photographed in her apartment:

photo: Lyn Devon, NYC, July ’08. © Graeme Mitchell

The act of letting go is a courageous thing b/c it is contingent on an honesty that is often brutal and seemingly dangerous. This relinquishing of control (or the illusion of it) is not to be confused with acts of self-destruction, as it is often those who seem bravest in their recklessness that are grasping tightest…(suicide (figurative in this case), someone once offered, is cowardly). No, what I’m speaking of is a less superficial and more difficult motion that is manifested externally more subtly than one would think. Probably b/c it ends up being a paradox. The further you commit to it’s uncertainty the more capable you may be to survive. But, again, this honesty I think is probably one of the great difficulties in life. Self-deception is a great infirmity of humans, a thing we are terribly crafty at.

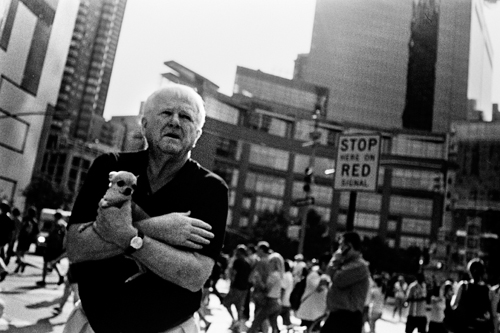

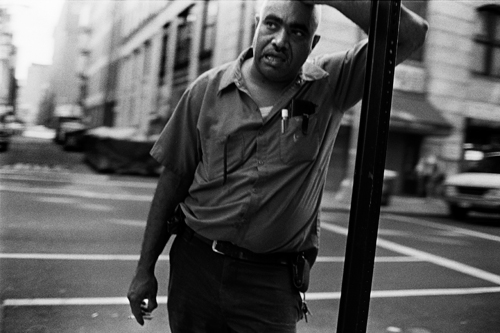

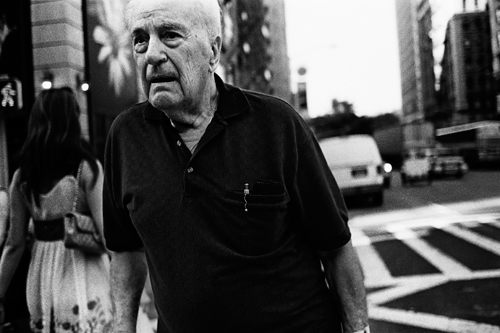

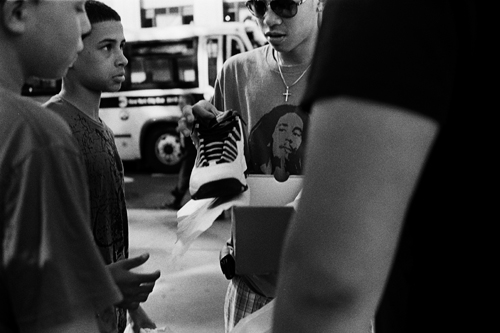

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

photo: ©Graeme Mitchell, 2008

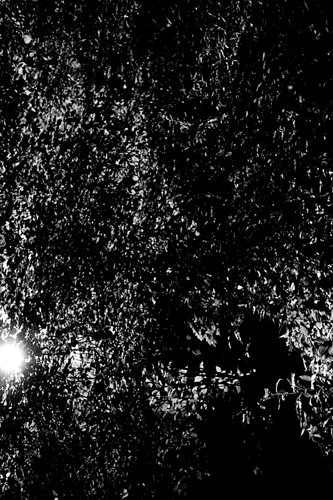

Uh, yeah, look, I’m going to need a little time to digest Bill Dane‘s work, to get a handle on what exactly it makes me feel. Right now, I have an inclination that I like it, and that he’s onto something. Other than that I’m leery to say much b/c I’ll quickly betray my lack of critical art theory learn-edness and nomenclature. But I do find something sinisterly uncanny in some of Dane’s work, which is to say I respond to it, which is to say I appreciate it…especially as a whole body of work.

Other than that, like I said, I’ll need some time.

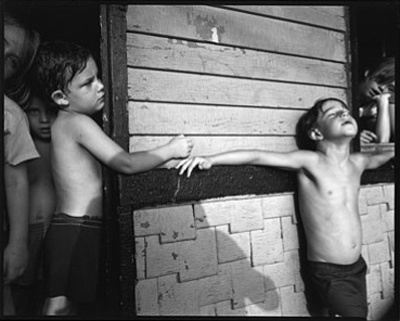

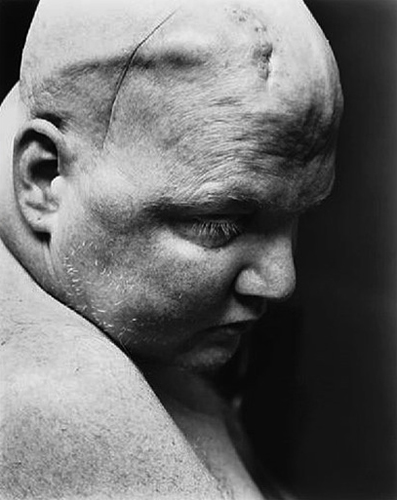

Nicholas Nixon gets a fair amount of respect in the photo and art community. Rightfully so, I think. These two photos of his blow me away. The first one I could only find a small jpg of, but still look closely at all the kids’ faces from side to side. Wonderful. And not to get geeky on the “how” of it, but that he does this with 8×10 is impressive.

photo: Covington, Kentucky, 1982. ©Nicholas Nixon.

photo: from Patients series. ©Nicholas Nixon.

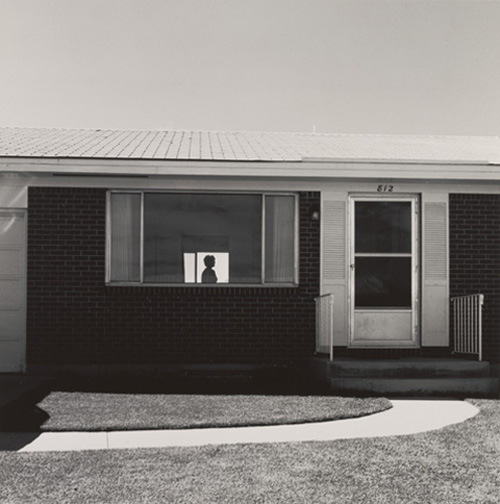

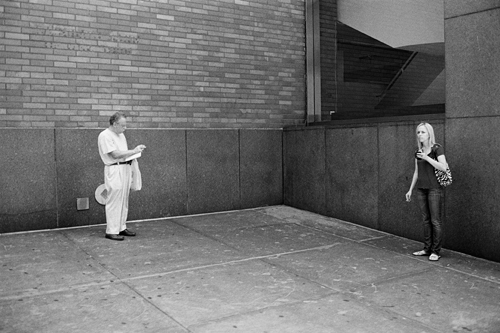

It was completely by chance (as is usually the case) that I happened upon Henry Wessel‘s work (more here). It’s the sort of work that I think a computer monitor doesn’t do justice and that needs to be experienced as a print. This probably has to do with what I see as a certain contemplative subtlety in his photographs. In a manner, they aren’t going to make an inference to you, or even a suggestion, but rather they’ll pleasantly leave you to your own devices.

Anyway, Wessel was a welcomed find today.

Photo: Southern California, 1985. ©Henry Wessel.

Photo: No. 12, 1996. ©Henry Wessel.

Maybe 100 times I’ve walked by Dashwood Books on Bond street w/o walking in until today, and boy that walking in was a bit of mistake as I was hoping to make it to the grocery store but instead managed to absolutely loose myself for over an hour in the small store. It’s a little space, rather sparse, housing only photography books, but every title is of such interest and quality I spent more time in there than I’d ever spent in the photography section of Strand. If you’re in NYC check it out. It’s right across the street from Chuck Close‘s studio. You might see him out sitting in the sun. And, well, I find a picture of Close’s studio entrance more intriguing than a picture of entrance to Dashwood Books, so…

photo: Chuck Close’s studio entrance, Bond St. NYC.

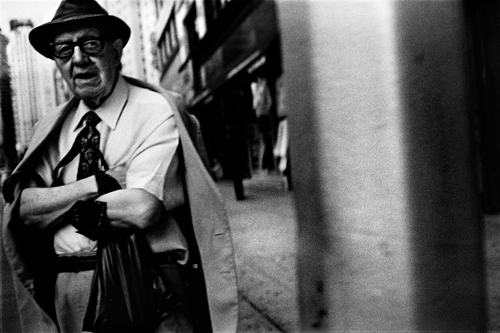

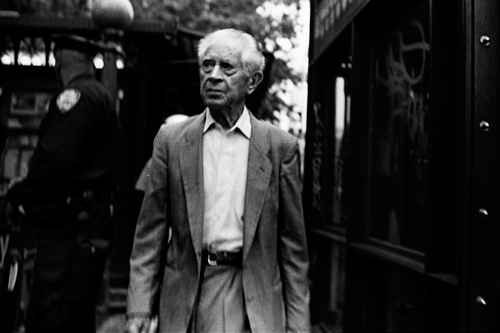

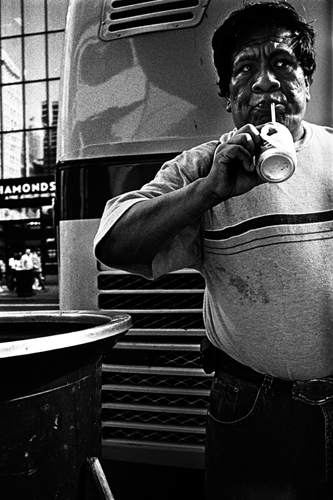

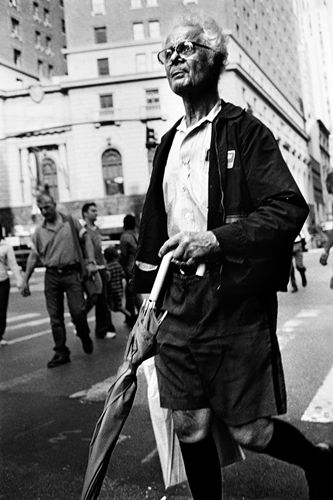

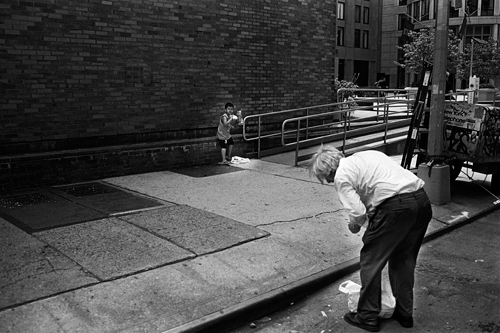

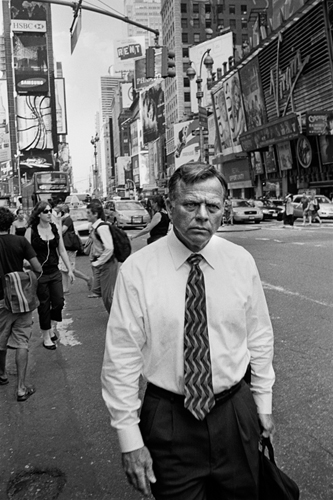

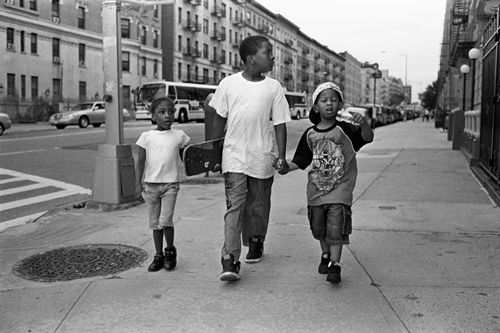

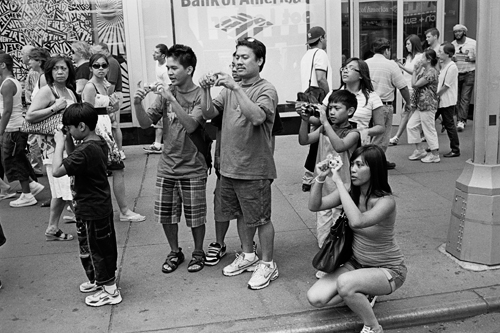

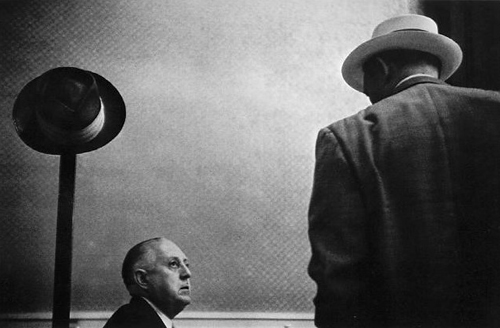

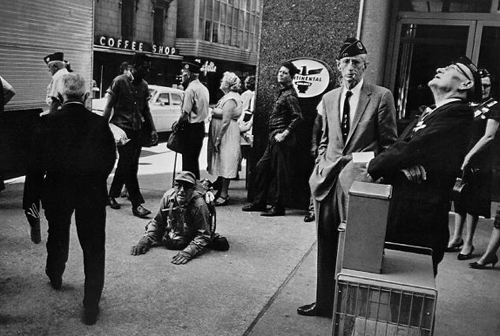

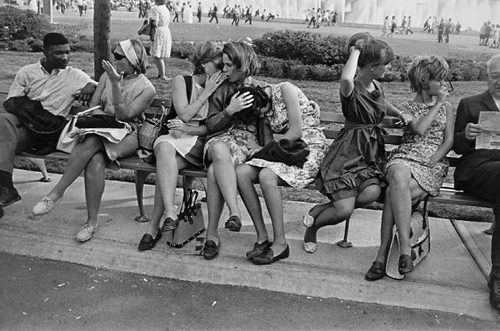

You could write a book on Winogrand and his short but unique life and the even more unique working process he had in creating what I think is a seminal and arguably one of the most representative bodies of classic American documentary photography ever produced. What I find most appealing in his photographs is how full of life they are, not only in literal content, but that there is a also sense Winogrand’s brimming taste for existence in them. Partially it comes from the archetypes that he was drawn to and how they effortlessly inspire narratives, but there’s more to it that that. It’s as though you become Winogrand in the shots, you take on his gaze, you know his intelligence and humors, you feel as he did and see the narrative he sees. This presence, the presence of the photographer, doesn’t ever shrink from the photographs, and thus the notion of the photograph as an artifact is also never lost. So a strength of these photographs is that they’re clearly one man’s fiction, like they’re written in first person, opposed to most photographs that are in the third person voice.  This is amazing and bizarre to me b/c it is a specific and a rare thing. Or at least it seems rare to me. Like I said, a book could be written, or at least a many-paged Master’s dissertation.

Furthermore, as far as street work goes, I think anyone who has ever tried to or even succeeded in photographing daily life would be humbled by what Winogrand achieved. I certainly am.

There’s a nice article on him, here, and for fun some pics of his M4, here.

photo: Untitled, 1950s. © Estate of Garry Winogrand

photo: American Legion Convention, Dallas, Texas, 1964. © Estate of Garry Winogrand

photo: World’s Fair, New York, 1964. © Estate of Garry Winogrand

(A side story I found interesting: when I was last at the MOMA I was with my friend, Benjamin. He enjoys photography more than you’re average Joe but is by no means versed in it or attempts any sort of sophistication in regards to it. In short, he enjoys whatever catches his eyes. Well, there were prints from any number of the greats hanging on the walls, including a series of maybe 10 pictures that Winogrand had shot at the NYC Zoo and the Coney Island Aquarium. If I recall they hung between Koudelka’s early work on the Gypsies and Diane Arbus‘ later work of the mentally handicapped Halloween outing. Imo, the Winogrand work was much more layered and much more difficult to appreciate. I’d have expected Benjamin to be drawn to Arbus’ otherness or Koudelka’s darkness. Yet, I watched him pass quickly over those and then come to a stand still at Winogrand’s photographs. He found them amazing. I complimented his taste, but I also became aware of something commonplace in Winogrands work that makes it something that anyone can be awed by, lacking pretense of high-art-conceit, which is why, I guess, I consider him the American street shooter, of the people and for the people. (Compare this to his more inaccessible contemporary Friedlander, who, btw, Benjamin didn’t take a second glance at…))

Finally, I caught this 2 part video at the 2point8 blog. It’s a clip of Winogrand with Bill Moyers:

First part,

And the second,

Unfortunately, this story was nixed by the mag we shot it for, so for the time being it’ll be exclusively published…right here!. Yes, here, where you can’t see the grain and blacks that’d make an old-timer proud, but I guess you’ll have to take my word for it that all that is nitty and gritty resides within.

As far as protocol if your story ever gets canceled: I’ve no idea.  In this case, I simply told my team sorry since they wouldn’t be getting tears from it, which I felt bad about. Then I started working on something else.

Keep struggling; it is what matters. Is what my old friend Mr. Diggles tells me in his earnestly paternal voice every time we talk. Indeed.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell 2008

photo: © Graeme Mitchell 2008

photo: © Graeme Mitchell 2008

photo: © Graeme Mitchell 2008

photo: © Graeme Mitchell 2008

photo: © Graeme Mitchell 2008

photo: © Graeme Mitchell 2008

photo: © Graeme Mitchell 2008

Credits:

Styled by Sara Dunn

Hair by Sarah Potempa w/ The Wall Group

Make-up by Ralph Siciliano

Model: Ania w/ Supreme

Location: The Hotel Chelsea

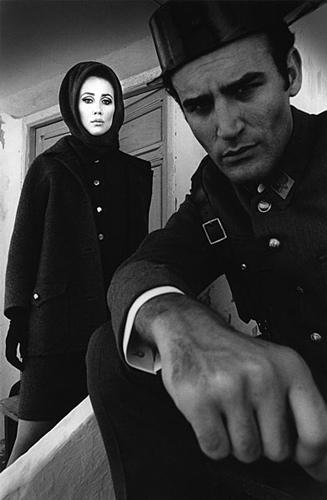

Jeanloup Sieff has my respect not only for the guttiness of his black and white aesthetic but also for his shooting nearly the entirety of it with, I believe, a 21mm lens on a Leica, including his fashion work. This I can only imagine must have taken a certain dedication and discipline. One lens might suggest a don’t-fix-it-if-it-ain’t-broke laziness, but trust me, there’s nothing lazy about doing good wide angle work, at all. Now, sure, you might counter that, say, Ralph Gibson manages equal personality in his B&W or you could point out the wide lenses William Klein’s early fashion work was shot on (i.e. that Seiff was just part of a gritty, wide angle generation), but there’s something else that set Seiff apart, and that was his not shying away from his love of a woman’s, to put it casually, ass. It was a form which he made beautiful in an apparent act of masculine adoration and desire but w/o ever letting this become anything less than a pulchritudinous depiction let alone a vulgar one.

Goes to show you that you can do whatever you want if you do it well.

photo: La femme est l’avenir de l’homme. 1995. © Jeanloup Seiff.

photo: Harper’s Bazaar. Madrid, 1966. © Jeanloup Seiff.

First, I’ll admit that I’m pinching this find from Dossier’s blog. I don’t spend enough time online to dig this stuff up on my own. Speaking of pinching, this scene from John Schlesinger’s film, Midnight Cowboy is ripe to be ripped off and made into a fashion story. (If you can do it. Do it! Play your cards right and you could build a fashion career on psychedelia right now. Which would be as ironic as the new John Varvatos in the old CBGB space on the Bowery. Sigh – alas, I think it’ll take an apocalypse of sorts (entirely feasible) before our post-modernist sensibilities of relative-truth and irony make the chance of a certainty – a sensibility unmistakable in this video clip – possible again. Until then the safest bet is inaction, un-care, or insanity…or likely a mix of the three. Or maybe there’s a fourth path too: engaging some Warhorlian high-intelligence. (Wait though, Dylan did write “Lay Lady Lay” for this film and it didn’t make the cut, which for some probably critically flawed reason on my part makes me think sentimentalizing the past is always a fallacy, b/c I can only imagine the reason for a song like “Lay Lady Lay” to be rejected would be a crude reason.))  Check out this clip anyway, for me its like a feverish susurration, and a self-aware requiem of an era to boot.

video: Party scene from Midnight Cowboy, 1969.

Summer’s humid-hard-hot-haze, and between 11am and 5pm the light is as ugly as hell. That’s why.

Larry Towell’s name was familiar to me b/c I knew he was with Magnum (here), but I’d not paid attention to his work until recently when I saw this series he shot years ago of his family in rural Ontario. In many ways this work remind me of Sally Mann, in location, in a certain affection, and in an idealic pastorial vision, but Towell’s work is less heavy handed visually. To it’s credit it’s simpler, and I say to it’s credit since the more subtle visual effect requires exceptional content – in general. But Towell’s work didn’t just strike me as being photographically excellent; more importantly, it reminded me of childhood and my own fond memories. Wonderful stuff.

(For more, there’s a multimedia essay on Magnum’s site, here.)

photo: Isaac’s First Swim, Lambton County, Ontario, Canada, 1996. ©Larry Towell/Magnum

photo: Baseball, Lambton County, Ontario, Canada, 1998. ©Larry Towell/Magnum

photo: Naomi in Hollow Tree with Cat, Ontario, Canada, 1990. ©Larry Towell/Magnum

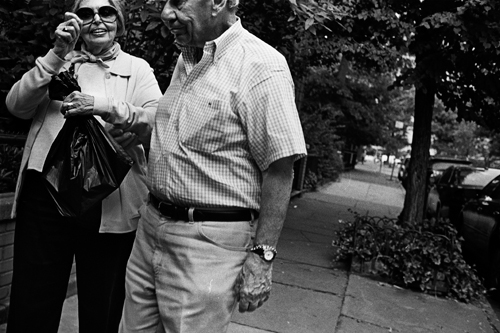

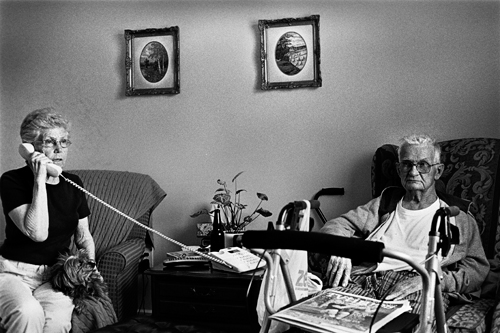

I guess I could say getting old is a sad process that betrays much of human nature, that family brings both the most joys and the most pains in life, that people rarely change and if so only on their own terms, that you can learn something from everyone around you…and so on. But instead, I’ll turn to Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (someone once said, and I paraphrase, that everything a man needs to know in life is in this book, a bit of a hyperbole probably, but I’m not sure it’s so far from the truth: reading it is like taking counsel from a prophet), so sitting next to my Grandpa, reading this novel, and thinking of the things you think of when in such a situation, a certain important passage from effected me (and I’m not religious in this sense, but just as much can be taken from this passage w/ a secular interpretation).

Much on earth is concealed from us, but in the place of it we have been granted a secret, a mysterious sense of our living bond with the other world, with the higher heavenly world, and the roots of our our thoughts and feelings are not here but in other worlds. That is why philosophers say it is impossibly on earth to conceive the essence of things. God took seeds from other worlds and sowed them on this earth, and raised up his garden; and everything that could sprout sprouted, and it lives and grows on through its sense of being in touch with other mysterious worlds; if this sense is weakened and destroyed in you, that which has grown up in you dies. Then you become indifferent to life, and even come to hate it. So I think.

-from The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Anyway, enough of that.

photo: my Grandpa, Lloyd Gauley, at the Sportsman Club, June 08. ©Graeme Mitchell.

I thought of just sharing the above picture, but here are two more.

photo: my Grandma and Grandpa in their chairs, June 08. ©Graeme Mitchell.

photo: my Grandma and Grandpa not in their chairs, June 08. ©Graeme Mitchell.