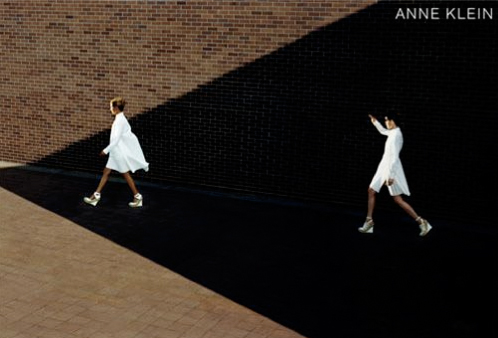

I really like these recent Anne Klein ads, put together by those fashion creatives at A/R and shot by Philip Lorca DiCorcia. (They may even be good enough to make up for the excruciatingly boring ads A/R and Patrick Demarchelier put out for Banana Republic this season…):

photo: Anne Klein S08 ads. Photographed by Philp Lorca DiCorcia.

photo: Anne Klein S08 ads. Photographed by Philp Lorca DiCorcia.

And of course, enjoy your Thanksgiving!

photo: Horncastle, England – A Turkey, 1994. ©Martin Parr/Magnum Photos.

I recalled reading a section in William T. Vollmann’s beautiful book Europe Central that focused on Käthe Kollwitz, a German artist that lived and created through both of the World Wars, but it wasn’t until last night that I came across a book on Kollwitz…and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t well up looking at the work of this artist who lost her son in WWI, her grandson in WWII, and who’s life was spent surrounded by war and death – I could feel the absolute necessity of her work, her tremendous empathy…and seeing what she felt, I counted my blessings.

Etching: “Woman with Dead Child” by Kathe Kollwitz.

Etching: “After the Battle” by Kathe Kollwitz.

I think Nathaniel Goldberg (w/ Art and Commerce) has been doing strong, beautiful work lately. I used to keep an eye out for his spreads in V magazine, always in studio, on white, and really well executed, but his recent spreads have shown his true reach and versatility. To name a few: a location fashion story for Vogue Italia, a nighttime location shoot with Ryan Gosling for GQ, a killer story in Vogue Nippon, etc etc etc. I can’t think of many photographer’s out there who are at the same time so specific and diverse… Most of all though, his work is right up my alley, a nice balance of playful, pretty, edgy, and still technically competent.

Well done, Nathaniel.

photo: from Vogue Italia Dec ’07. ©Nathaniel Goldberg, (image found at Art and Commerce’s website).

photo: from GQ Nov ’07. ©Nathaniel Goldberg, (image found at Art and Commerce’s website).

That second image of Gosling in the diner is a nice homage to Edward Hooper’s famous Nighthawks:

painting: Nighthawks, 1942, by Edward Hooper.

I came by a hefty book of Lartigue’s work and walked away absolutely humbled. B/c, you see, he did something few people ever manage, that is, he did something truly authentic. And from what I can tell, he did it with neither chutzpah nor hubris…nope, he just did it.

I repeat: absolutely humbled.

I see all those shoots David Sims does of models jumping across the set, the same ones that Hiro did before him, and Avedon before he…see these and consider Lartigue inventing that sensibility as a 10 year old kid at the beginning of the 20th century, shooting his sister and cousins jumping through the air. It makes implicit the shoulders we stand upon and the rarity unique ideas are.

I want to quote from Avedon’s (an acquaintance of Lartigue’s) afterword to this book, since I wouldn’t pretend to be able to add anything more:

I think Jacques Henri Lartigue is the most deceptively simple and penetrating photographer in the short…embarrassing history of that so-called art. While his predecessors and contemporaries were creating and serving traditions he did what no photographer has done before or since. He photographed his own life. It was as if he knew instinctively and from the very beginning that the real secrets lay in the small things. And it was a kind of wisdom – so much deeper than training and often perverted by it – that he never lost. There is almost no one in this book who isn’t a friend…no moment that wasn’t a private one.

Lartigue never exhibited his pictures until 1962. He never thought of himself as a photographer. It was just something he did every day…ever day for seventy years. Out of love of it. And every day his eye refined and his skill with a camera grew. He was an amateur…never burdened by ambition or the need to be a serious person.

But it would be a great mistake to credit his artistry merely to the fact that he was not corrupted by professionalism. Or to say that his work was the product of accident..that his photographs are extraordinary because the people around him were. Or the time in which he lived. Hundreds of children with similar backgrounds were given cameras in those days – but they never became Lartigues. And accidents aren’t capricious. They just don’t happen that often. They can’t produce a single body of work so consistently brilliant. Lartigue is not a reporter and his best photographs are not those gained by chance.

From the earliest possible age Lartigue kept a little diary. At the top of each page there was always a little drawing of the sun or a cloud…and some initials: T.B., B., T.T.B. They stood for Trés beau. Beau. Trés trés beau… That was the weather. It was always a good day. It almost never rained. Ever… And then there would be a quick description of what he did that day. Who visited the house. Where they went… And half the page devoted to drawings of what he’d photographed, because developing was a very risky process and often the pictures didn’t come out. So, afraid that he might never see the pictures that he’d taken, he would draw from memory what he’d photographed. And in the diaries, which went on for many years, you can see the photographs that have since become masterpieces…drawn. And the miracle of these little drawings is that he had captured exactly the way a scarf had been caught by the wind the moment he clicked the shutter. And they’re accurate. Absolutely accurate. Which means a perfect memory…and a complete sense of what he wanted. And this obsessiveness went on every year of his life. The files. The scrapbooks. They’re all over the apartment. The perfection of those files. In a second, he can find any glass negative…1911- neatly kept in perfect condition.

–Richard Avedon. Paris. February 15, 1970. (From afterword to Diary of a Century: Jacques Henri Lartigue. New York: Viking Press, 1970.)

Avedon continues, but I don’t want to belabor it any more than I already have. The point is, I think that in Lartigue’s work and in what Avedon writes of Lartigue, there is a great deal for anyone to learn, and not so much about taking photographs but more simply (or maybe more complexly) about living life.

photo: Sala Au rocher de la vierge. Août 1927. Biarritz. ©Jacques Henri Lartigue.

photo: Zissou, Rouzat. 1911. ©Jacques Henri Lartigue.

photo: My cousin Simone. 1913. ©Jacques Henri Lartigue.

photo: Zissou’s bobsled with wheels, after the bend by the gate, Rouzat, August 1908. ©Jacques Henri Lartigue.

Then of course there is Lartigue’s most famous photo that I’ve posted before while discussing Irving Penn’s refined compositions, here.

And finally, fittingly, a picture of Lartigue and Avedon together. Such a lovely picture, you can see the pairs genuine kinship with one another, Lartigue’s hand on Avedon’s shoulder as the young Avedon goofs, possibly in a gesture expressing his opinion on the immensity of Lartigue’s mind and creativity.

photo: Richard Avedon and Jacques Henri Lartigue, New York, November 1966 (photograph taken by Florette, Lartigue’s wife).

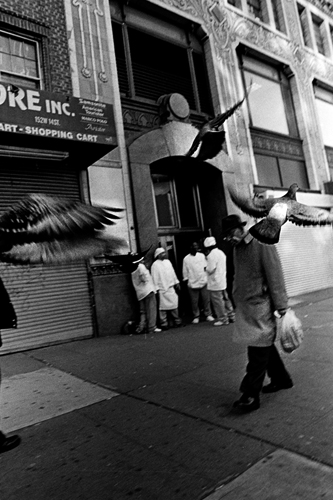

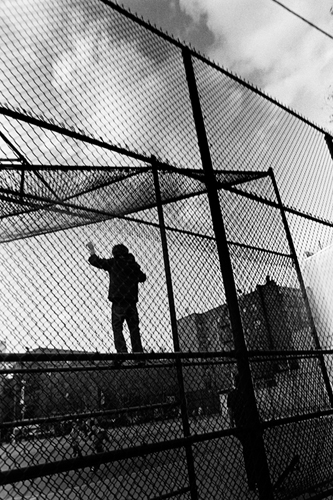

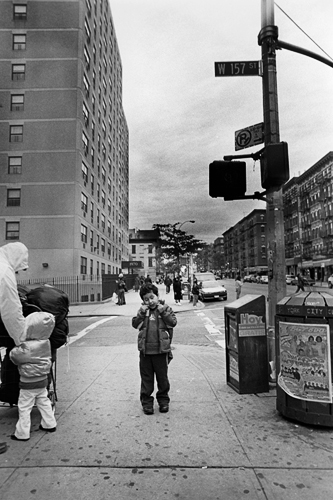

Consider these postcards I’ve sent you. Wish you were here! scrawled across them.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

These too, are all taken while near by my apartment.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

These, on the other hand, were not taken around my apt. They actually surprised me. Finding an old forgotten roll of film accidentally is like finding that old forgotten $5 in your pant pocket.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

And then back the NYC:

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

All of these pictures were taken in and around where I live while walking to the train or to the store or etc:

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

I started to write something here about photography and solipsisms and the idea of breaching that cusp that divides that which we can mutter and that which leaves us mute. B/c, I was thinking, don’t we all long for that moment when that insatiable pursuit to know is, briefly, assuaged? Then, painfully aware that my ardor more often than not belies my reason, and also recognizing that epiphanies usurp us, not the other way around, I thought it best to just try and post some decent pictures:

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

Late Friday while imbibing with some friends in the East Village, I received a text from another friend who lives on the West Coast. He is, at heart, both a poet and a sufferer. So it’s not surprising that the text read, “‘to know what is enough one must first know what is more than enough’ -William Blake.”

That text has nothing to do with these pictures, as far as I can tell.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: © Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

I once saw a cartoon of a writer at a desk with a large manuscript laying finished next to his typewriter. The caption read, “I have just written the great American novel. I will now burn the only existing manuscript and write an autobiography of how that made me feel.”

The documentation of process has become commonplace within every field from art to commerce. This sensibility, as most know, is the ramifications and remnants of some of the basis’ of post-modern thought. What was once the profound work of Gass, Barth, and Vonnegut is now modus apparatus of self-promotion.

But before I digress into something about Hollywood as the savior of the metanarrative, allow me this guilty moment of indulgence in what is now common, make room on the bandwagon(!): these are some first frames of rolls from NYC Journal, a look into that moment when I enthusiastically wind in past the film leader to begin afresh.

(And I won’t even bother with the copyright info. Take them. They’re yours.)

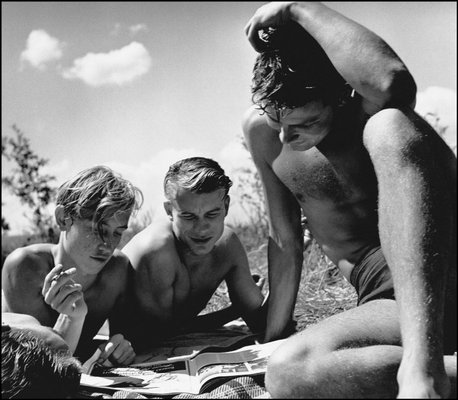

I’ve long been a fan of Bruce Weber’s work. He seems to stand alone in his genre; actually, his work is near a genre in itself: both in subject and technique he sometimes appears to have created his own path. So it’s interesting to see work that came before and, I imagine, informed Bruce. Case in point Herbert List (w/ Magnum), who not only had a proclivity for the male form in a classical aesthetic and for a certain boys at play sensibility, if you will, but his work also has a similar feel technically to that Bruce is now doing. Frankly, if you’d shown me these top two pictures of List’s, I’d of assumed they were from a recent A&F catalog.

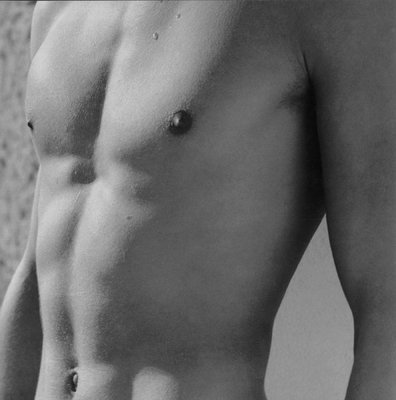

Needless to say, List’s photographs are beautiful. This first photo especially:

photo: Wrestling Boys, 1933. ©Herbert List/Magnum.

photo: Torso of Young Man, c. 1938. ©Herbert List/Magnum.

photo: Friends at Lake Starnberger, 1946. ©Herbert List/Magnum.