As usual this post begins in a bookstore, where I came upon Sally Mann’s beautiful and instantly classic book, Immediate Family. This book and I have crossed paths a number of times before, but up until now while looking at it I’d never thought of Caddy from Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Now I can’t seem to separate them. If you know that Faulkner once wrote, to paraphrase, that the entire story of The Sound and the Fury arose from imagining the sight of a girl in dirty underwear climbing a tree, then the parallel may make sense to you too. That Mann and Faulkner’s works are both so intrinsically tied to the South and the gothicism of the South is also an obvious similarity.

Anyway, if you’ve not taken up either of these books, I suggest to.

photo: from Immediate Family (1990), © Sally Mann.

photo: from Immediate Family (1990), © Sally Mann.

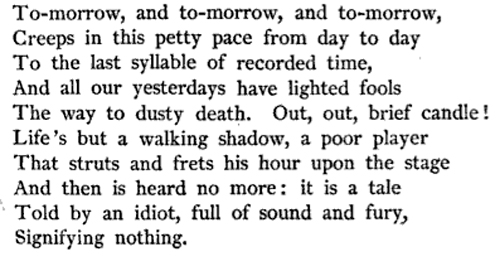

On a separate note, it’s well known too that the title of The Sound and the Fury came from the Old Bards, Macbeth. I’ve always adored the passage, which is a soliloquy of Macbeth’s (and also a friendly reminder to read more Shakespeare):

text: Macbeth, Act V, Scene V. By William Shakespeare.

This is an update to this recent post. It’s possible you’ve already seen these as I also put them up on my portfolio page. Right now I’m waiting for the final edit from the creative director, but during this wait I’ll begin working casually on a few of the images that interested me immediately. I’ll play with different options for final prints, let them sit, digest, rework them, repeat. So by the time I do get the final edit I have a clear direction as to how I plan on interpreting the negative and can get it out to them quickly.

photo: Covet Spring ’08, ©Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

photo: Covet Spring ’08, ©Graeme Mitchell, 2007.

My new portfolio site has just been turned on, launched, gone hot, whatever the kids are saying today.

Take a gander at www.graememitchell.com.

A few things I wish to note:

First, once again, the one-man-web-think-tank, Benjamin Diggles takes all the credit for putting this together, design and code. See his portfolio here, his music here, his blog here, and the company he works for here – (I’m always in awe at how many projects Benjamin is working on at any given moment). Benjamin and I have known each other since we were 9, and as far as I’m concerned we’re brothers, so I’m proud that he’s the one working on this, means a lot to me.

Second, I want to thank all the photo editors, art buyers, agents, and so on and so forth that took the time to give constructive criticism regarding my previous site. I’m not a web head, nor even know that much about it, so the opinions from those people who look at pics online all day was and is invaluable. I think it’s great when people in those positions take the time to offer unprompted ideas to improve something like presentation.

Last, as I’ve told Benjamin 85 times, I’m really excited about this site. For what it’s worth coming from someone who isn’t web oriented, I think it’s perfect for my work.

Enjoy!

Late late last night I was looking through MOMA’s collection of photography. My initial interest was looking at work by unknown photographers, unattributed work, since through the day I’d had this line of thought in regards to identity, reflection of self, authorship, etc, that I was unable to order or find completion in, and viewing work w/o authors seemed like it may prompt uniformity in the line of thought, if you could call it a line. Though a reasonable hope, it ended up being false hope. But I kept clicking through the collection.

And as I ran later and later into the collection I noticed a photographer’s name over and over, Lee Friedlander. I know the name Friedlander, know he’s still alive, know he shoots documentry work of sorts, but even knowing these things I’d never actually looked at or thought about his work. So I did. And I came away thinking that he uses the camera in an entirely imaginative and creative manner that isn’t, how should I say, contrived, or maybe that there appears to be a lack of self-consciousness in his images is a more appropriate phrasing. Instead, his pictures, especially his later works, seem wholly visceral (and b/c of this somehow unmitigated, as you can understand). And to me work that is visceral is most often brave, and brave work is what any artist should strive for.

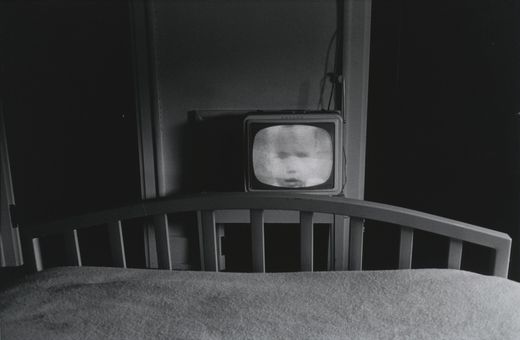

First, his series of TVs on in empty rooms. I love these. I wish I’d taken these. But I’m acutely aware that any picture of a TV in an empty room will always be in the footsteps of Friedlander.

photo: Galex, Virginia. 1962. © Lee Friedlander, 2007.

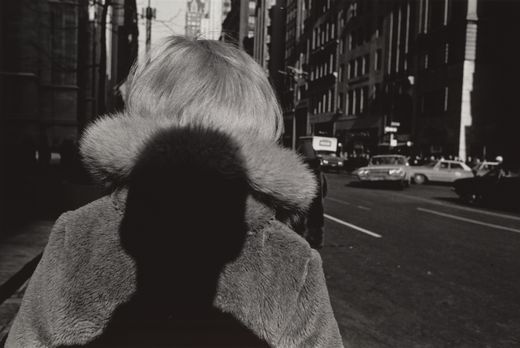

Then there are his pictures that his own shadow plays an integral part in. I love these. I wish I’d taken these. But I’m acutely aware that any picture that the photographer’s shadow plays an integral part in will always be in the footsteps of Friedlander.

photo: New York City. 1966. © Lee Friedlander, 2007.

Then, similarly, there are his images with his reflection. I love these. I wish I’d taken these. But I’m acutely aware that any picture with the photographer’s reflection in a window will always be in the footsteps of Friedlander.

photo: Denver, Colorado. 1998. © Lee Friedlander, 2007.

Then, finally, there are his self portraits. Often behind sparse foliage. Initially I did not love these and did not wish I’d done them. But after going through his body of work and seeing how he’d arrived here. I did love them and did wish I’d done them. But I’m acutely aware that any self portrait of photographer behind sparse foliage will always be in the footsteps of Friedlander.

photo: California. 1997. © Lee Friedlander, 2007.

Now I wish to return to the initial topic of this post, and that was my researching unattributed works to better understand and to explore ideas of identity, image, self awareness, reflection, etc. Initially, I asked, what are we but a series of ideas and events that we’ve compiled? Then I thought of self-projection, and thus authorship and began to ask if something in the specific realm of the artist could elucidate a more universal premise. You get the idea. I too quickly concluded the MOMA collection wasn’t going to be much inspiration.

Then Friedlander distracted me.

Then I went to bed.

Then at some point late last night staring at the too yellow street light out my window, I realized Friedlander’s work was what I’d been looking for the entire time. Once I got past wishing I’d taken his pictures, I saw the obvious: that identity, reflection, self-awarenesses, and so forth, are all central issues he’s confronting. What I’ve yet to get my head around is whether he is simplifying or complicating these issues. Is he projecting self, or raising questions around self? Is his work a testimony, a stamp, a marking, a graffiti on the wall exclaiming, Lee was here? Or is it an obscuring of self, a questioning of what makes self up, the photographer/author apparent in his work, meta, post-mod, self as a shadow on others, as a cracked reflection in a store window, as a grotesque figure within yet obviously different from nature?

I don’t know, but it seems like something worth thinking about.

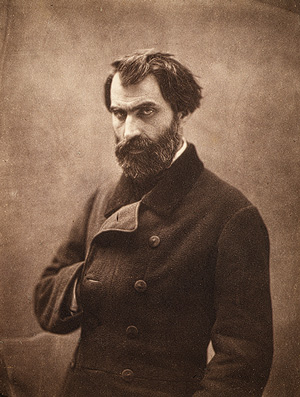

It’s incredible for me to think of Nadar doing this kind of work, taking these kind of portraits, that in sensibility feel so modern, over 150 years ago. I try and imagine him in Paris during the peak of Romanticism, mixing with and photographing the likes of Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier, and living during this pique of beauty and aesthetic. Somehow this must come through in his portraits, yes? Maybe in the sense of the theatrical, b/c I’d guess, despite the admirable earnestness of their ideals, the Romantics might have been guilty of theatrics. Just as so many artists are. Regardless, there’s a sense that not only did Nadar know exactly what he was doing, but he also captured a certain spirit of a time and idea – which is something, considering he was working with photography in it’s infantile stages…though I guess the opposite line of thought could be true: that maybe such work is easier borne if uninhibited from the history of what’s come before… It doesn’t really matter. Just see that, as far as portraiture goes, there is a lot to learn from Nadar. (Mind you, I really know nothing about him historically, nor much about photographs history, so…)

photo: Eugene Pelletan, 1855-1859, by Nadar.

photo: Pierrot Laughing, 1855, by Nadar.

To close, the Baudelaire poem, Au Lecteur, or To the Reader:

Folly, error, sin, avarice

Occupy our minds and labor our bodies,

And we feed our pleasant remorse

As beggars nourish their vermin.Our sins are obstinate, our repentance is faint;

We exact a high price for our confessions,

And we gaily return to the miry path,

Believing that base tears wash away all our stains.On the pillow of evil Satan, Trismegist,

Incessantly lulls our enchanted minds,

And the noble metal of our will

Is wholly vaporized by this wise alchemist.The Devil holds the strings which move us!

In repugnant things we discover charms;

Every day we descend a step further toward Hell,

Without horror, through gloom that stinks.Like a penniless rake who with kisses and bites

Tortures the breast of an old prostitute,

We steal as we pass by a clandestine pleasure

That we squeeze very hard like a dried up orange.Serried, swarming, like a million maggots,

A legion of Demons carouses in our brains,

And when we breathe, Death, that unseen river,

Descends into our lungs with muffled wails.If rape, poison, daggers, arson

Have not yet embroidered with their pleasing designs

The banal canvas of our pitiable lives,

It is because our souls have not enough boldness.But among the jackals, the panthers, the bitch hounds,

The apes, the scorpions, the vultures, the serpents,

The yelping, howling, growling, crawling monsters,

In the filthy menagerie of our vices,There is one more ugly, more wicked, more filthy!

Although he makes neither great gestures nor great cries,

He would willingly make of the earth a shambles

And, in a yawn, swallow the world;He is Ennui! — His eye watery as though with tears,

He dreams of scaffolds as he smokes his hookah pipe.

You know him reader, that refined monster,

— Hypocritish reader, — my fellow, — my brother!-Charles Baudelaire

Translated by: William Aggeler, The Flowers of Evil (Fresno, CA: Academy Library Guild, 1954)